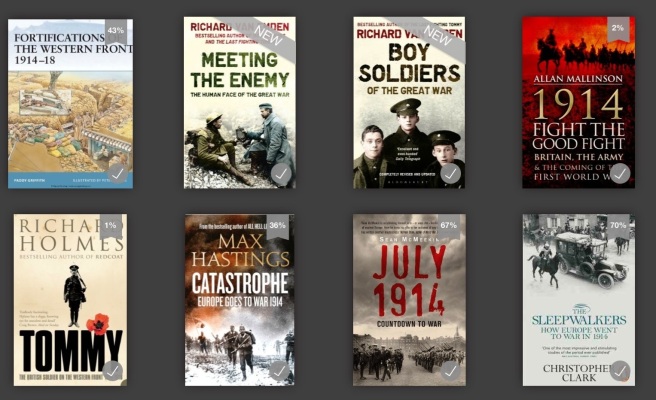

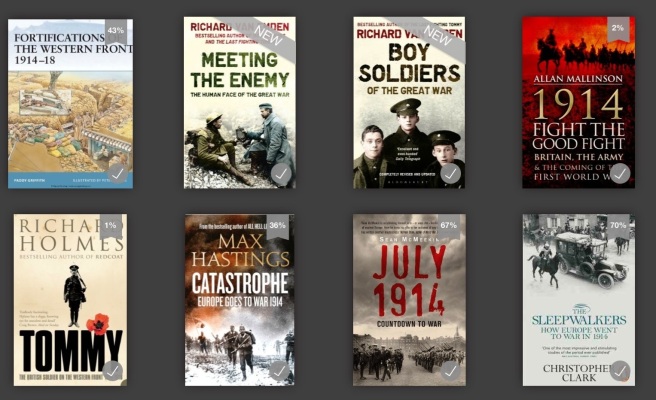

Although Kindle suggests otherwise I have read most of these. I have read Christopher Clark ‘The Sleepwalkers. How europe went to war in 1914’ twice and am now reducing copious notes down to a cribsheet or revision notes. In due course I want to generate a series of multiple-choice questions on the QStream patform and a SimpleMind mindmap. By then the info may have stuck. According to Kindle 70% read takes me to the reference section of this 600+ page book. A third complete read is likely as I feel I can trust this Cambridge professor of history to be accurate and up to date.

‘Boy Soldiers’ I have read as a paperback. I find the eBook version more versatile – not least having it in my pocket at all times to cross reference. If there is a way to interest teenage boys in the history of World War One this is it. ‘Meeting the Enemy’ I have just downloaded as Richard van Emden is an easy and authoritative voice. It’ll add colour and insight to my own grandfather’s recollections of how a ‘Jerry’ wandered into their pillbox one foggy October or November morning in 1917.

I have several books on women and the First World War – anthologies and diaries. Often revealing for the common experience rather than anything that is startlingly different.

Others I have read to hear the same narrative with a different voice.

Sean McMeekin on the July Crisis is thorough and more tightly chronological than Clark who spends more time with each country. Another way to do this might be as a kind of bibliography – each of the sixteen or so key players profiled in detail relating to decisions taken in 1914. By the time I have read Allan Mallinson the chronology and landscape of the events leading to conflict in 1914 ought to be clear in my mind. This is how I learn – multiple voices on the same material expressed in a slightly different way – what resonates are the moments and conclusions that they have in common, or something finally makes sense when I hear it expressed in a certain way, or a new insight or nugget of information is offered.

Max Hastings, understandably given his journalism background, composes his narrative like a journalist dipping into anecdotes and gossip. Whilst adding colour and noise some of the history is wrong (the dates of and significance of Russia’s preparatory and pre-mobilization plans) and very little is referenced, which I find odd as he had to get his information from somewhere. Already I am hearing a phrase or fact here and there that I recognise from documenaries and the basic and sometimes dated texts – all should be properly cited but is not. This feels like an opportunity to cash in on 1914-1918 interest. However it does offer something new – largelly what the papers were reporting, with all the selection for sensationalism or curiosity, bias, hyperbole or fog that this means.

Richard Holmes I’ve read in print. Like Lyn Macdonald I find he offers an excellent perspective from the soldier’s point of view.

Paddy Griffith comes recommended courtesy of comments in an Amazon Review. Not this book in particular, but the author and the many books he has written.

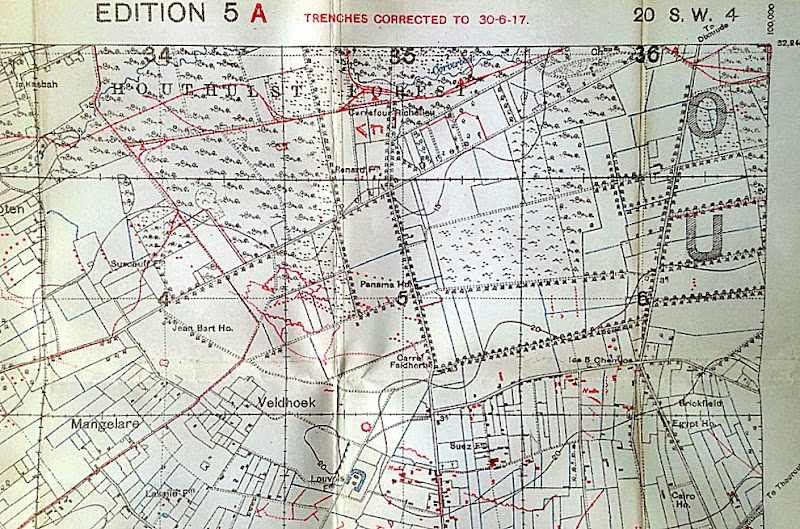

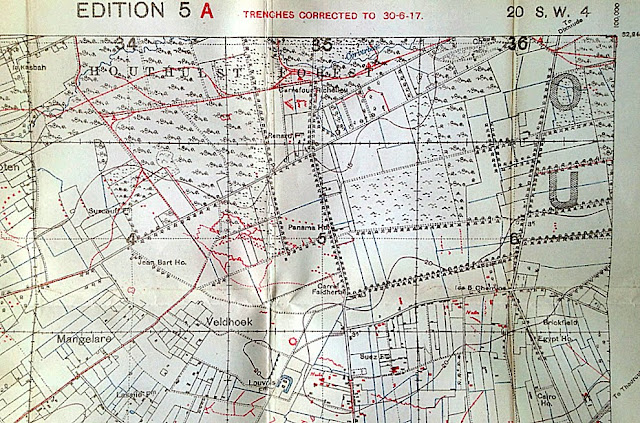

Meanwhile I colour this with the Hew Strachan inspired documentary series on the First World War (on YouTube) and others, along with the film ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ and visits to battlefields (Ypres) and museums.

Read on a period in history until you hear the people speak? I can listen to several hours of interviews with my grandfather – or those done with hundreds of veterans over the decades. I like my grandfather’s perspective – it was a job to be done and he wanted to get on with it until the job was done.

A couple of things I feel convinced of from the above reading:

Germany was hemmed in and ultimately left with no choice but to attack on all fronts – Serbia, Austria-Hungary, Russia and even France started this war.

Once in play the brutal behaviour of Austria in Serbia, and especially of Germany in Bulgaria, revealed a a national character, whether fed from the top or inculcated in the soldiers, that had to be stopped.

And the most trammeled and set upon?

Belgium

So much for neutrality. Did this make Germany (and potentially France) think of Begium as neutered?

As we approach the centenerary of the First World War what will each nation have to say?

Has Germany gone quiet?

What can Serbia say?

And the Turks?

Let alone Commonwealth and Colonial peoples and nations?

What does it say about humankind and nationhood?

It’s not as if we don’t still live with the consequences of that war and the second world war.